The following was Patagonia’s response to some questions about materials and testing which was posted in 2005 to a public forum. Most of this article matches my personal experience and still seems valid today.

Mark Verber

Innovation, that steamroller of change, has, over the past five years completely redefined the way people dress for the mountains – to the benefit of alpinists, anglers, snowsliders and endurance athletes who can stay out more comfortably and for longer stretches.

But innovation has also brought confusion to the retail floor: claims and counterclaims abound. How does one make sense of the multitude of marketing messages?

The goal of this document is to help clear the fog, to go back to first and basic principles, to concentrate on the customer’s essential question: For the activities I pursue in the conditions I encounter, how do I stay warm and dry?

That’s Patagonia’s focus when we design. What’s the need? Then, how do we create a product that will meet it?

Technology and Change: What’s It Good For?

At Patagonia, technology is secondary: it’s backstory. A means to an end. Only when we come to a full understanding of the performance requirements for a garment do we dive into the details: choosing the elements of the fabric package, but also – and this can get lost in the current discussion – construction, features, fit.

When technology comes second and performance goals first, “off-the-shelf” fabrics rarely fit the bill. An existing fabric more often than not has some of the performance characteristics we require but lacks others. So we’ll work with the supplier to tweak it: change some element of the construction, or use a different lining or finish.

Our more successful concoctions get adopted by the industry as a whole. The shelves and racks of outdoor stores bulge with non-Patagonia products made of fabrics we helped develop over the years: among others, Malden’s Polartec 100, 200, 300, Power Stretch, Thermal Pro, and Recycled Polartec fleece; Dyersburg’s Eco Fleece; Gore’s Activent and Windstopper fabrics; Nextec’s Epic water-repellent finish.

In any given year, we work as closely as we can with over 80 mills and suppliers. These relationships, built up over 30 years, are important to us. But the customer’s need comes first: Patagonia will always employ the best, most appropriate fabrics (and construction, features, fit) for an intended use. When a better technology comes along, or when we can help create something better, we do.

Sometimes – as is the case now with shells – the rate of change is dizzying. Our Dimension Jacket, for instance, at the time of its 2001 introduction, was more breathable, more wind- and water-resistant and quicker drying than any competing soft shell on the market. It won industry and customer accolades and sold well. Only two years later, we changed both the fabric and surface treatment – to achieve an 80% increase in breathability and a 20% reduction in weight.

On the other hand: Capilene®. For the past 18 years we have worked with one supplier to continually improve the performance of our Midweight base layer. And although the 2004 Midweight Crew is in every way better than its 1986 original, the DNA match still looks pretty close.

Have we looked at alternatives? Of course. Have we tested all the new underwear fabrics from all suppliers as they’ve come on the market? Yes. Some have great stories behind them, but none pan out to our satisfaction. After 18 years, the only garment that outperforms Midweight Capilene, for some conditions and some uses, is an appropriate Regulator® base layer.

Capilene technology is not complex, which brings us to a related point. Although we work hard to develop the best possible fabric package for each product, why overbuild? The ice climber, for instance, needs the stretch, high compressibility, low weight, extended DWR performance and breathability that H2No® Stretch HB fabric lends the Stretch Element Jacket. But many of those characteristics are overkill for even the most committed alpine skier or patroller, for whom the Primo Jacket offers more sport-specific features and an excellent, more downhill-appropriate fabric: in this case, Gore® XCR®.

The Patagonia Lab: What Goes On Behind the Swinging Doors?

We test ALL emerging fabrics and technologies, whether we’re involved in their development or not. Last year, we conducted 3,796 tests on 836 fabrics in development. Of those, only 56 performed well enough to be adopted. The lab also conducted nearly 15,000 tests on production lots to ensure that adopted fabrics perform to expectations.

The qualities we test for include breaking strength, abrasion and tear resistance, bonding strength, breathability, zipper strength, compressibility, water repellency, wind resistance, wicking speed, colorfastness and garment durability in wet conditions.

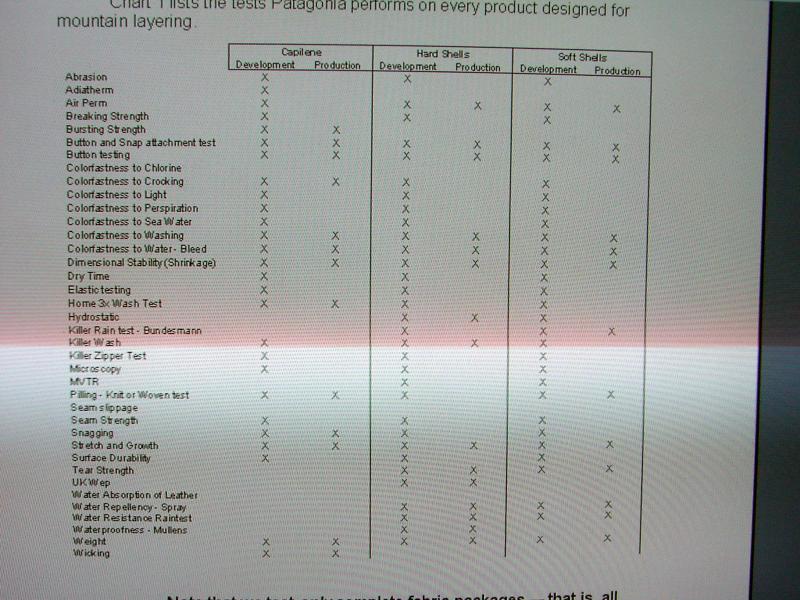

Chart 1 lists the tests Patagonia performs on every product designed for mountain layering.

Note that we test only complete fabric packages – that is, all the fabric components used together in a final garment. It’s useless to test, for instance, a waterproof/breathable barrier without its substrate. The barrier will never be used alone.

And we test to predict performance in the field, not to generate winning numbers. The tests derive initial, preliminary answers to the important questions: How does one component of a fabric package affect the garment’s overall performance? How will this overall package perform in a range of conditions, and after a full season of use?

Testing for long-term performance is especially important because many fabrics that ace their exams when new, and would perform beautifully on the sales floor should the roof leak, but deteriorate rapidly in mountain conditions.

What are some of the most important tests? What do they signify for end use? We’ll take you through a few of them and, along the way, point out what they can’t tell you.

What is the PSI Test for waterproofness?

PSI (pressure expressed in pounds per square inch) is a measure of the strength of a waterproof barrier before water penetrates. A person weighing 165 pounds, for instance, exerts about 16 PSI on the knees, when kneeling. The military standard for waterproofness is 25-PSI, the industry standard – and practice – much higher.

Patagonia actually performs two tests to check a barrier’s waterproofness: the traditional Mullens Test and, more importantly, the Hydro Test that yields PSI after extended performance. All barrier technologies used by the outdoor industry are better than waterproof when new. And they all degrade with time, and at greatly variable rates. We want long-term performance, not a superhigh off-the-shelf rating that plunges under a bit of rain.

We have rejected, for precisely this reason, the newer lower-priced 2.5-layer hard shell packages, including those adopted by other manufacturers, in favor of an H2No package that maintains its waterproofness long after others have noticeably deteriorated.

The H2No 2.5 layer package has a superior surface water repellent; a barrier less prone to contamination from dirt and oil, which can “draw” moisture through a fabric or membrane via capillary action (as well as reduce breathability). In place of standard coating or dots, a slightly raised, internal 3-D matrix provides durable service (as well as better wicking and compressibility).

How does MVTR indicate breathability?

Moisture Vapor Transport Rate (MVTR) measures the ability of a fabric to pass moisture from the inside to the outside of breathability in grams per square meter per day. Unfortunately, dozens of test methods are used to measure this: beware of direct comparisons of fabrics tested by different methods.

Patagonia uses an ASTM protocol known as E96 that allows us to create a pressure differential between the inside and outside of the fabric, one that is reasonably identical to conditions you encounter in the real world (i.e., E96 test results correlate consistently with those of our field testers). It’s the only test that does not introduce artificial factors like excess heat and pressure. E96 also allows us to measure MVTR without regard to air permeability (which we measure separately): this gives us a true measure of a fabric’s inherent ability to move moisture. And we can test two levels of exertion, low and high.

We’ve developed our own MVTR chamber, one recognized by independent research facilities for its excellence. Our tests are highly repeatable and produce consistent results.

How does CFM measure wind resistance?

Cubic feet per minute per square meter (CFM) is a measure of the wind resistance or air permeability of a fabric. The higher the CFM, the greater the volume of air passing through.

When hard shells dominated the landscape, discussions about CFM didn’t come up. Traditional barriers like H2NO, Gore, Triple Point, Entrant, and other respectable waterproof breathable technologies all have a 0 CFM rating. They are absolutely windproof.

With the advent of soft shells and more breathable fabrics, the air permeability argument becomes complicated, sometimes heated.

Traditional layering has always taught the “vapor barrier warmth” concept. That is, maintain a (windproof) stable dead air space next to skin and you will stay warmer. That’s true, if you’re watching football game from the stands in November.

But what happens when you’re pounding uphill to the ridge before someone else sneaks into that untracked line of new powder? You can use a bit of convective heat loss; and you need more breathability to move the extra moisture you create through exertion.

And a fabric with 0 CFM doesn’t provide it. We’ve found that fabrics that measure as much as 5 CFM are still functionally windproof: that is, you don’t feel the breeze come through. And they afford much greater comfort on the uphill. So we use 1-5 CFM as our standard for weather-protective soft shells (Mixmaster, Dimension, Dragonfly, etc.)

Shells for higher exertion activities (e.g. Slingshot, Super Guide Pants, Talus Pants) must be even more breathable. For these products we hold to a comfortably wind-resistant, but not windproof, standard of 10-15 CFM.

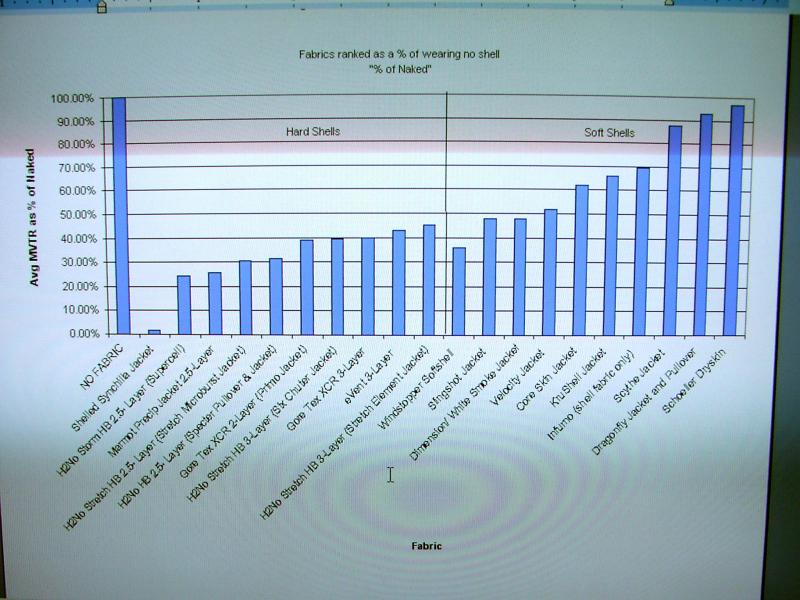

Beyond this, we don’t go. We don’t produce shell fabrics with a higher CFM (say, 15-20) because our field test shows that further gains in breathability don’t offset the heat loss from wind penetration. (See Schoeller Dryskin on the chart on the next page- offering high breathability, but not enough wind protection) The goal is: both warm and dry.

At the other end of the scale, as mentioned, we don’t make 0 CFM soft shells. What’s the point of a soft shell that doesn’t breathe better than a hard shell?

What is Percent of Naked?

Patagonia has developed an intuitive way of evaluating overall breathability called “Percent of Naked,” in which we directly compare the combined MVTR and CFM data of a fabric to data produced by the same equipment, but without fabric. [Love of the idea of this, but just how do we use equipment with no fabric: sounds more than naked, positively immaterial] This gives us a base line to compare individual fabric performance to the holy grail, the 100% of comfort and breathability: how you feel naked in your living room with the thermostat at 72 degrees.

How does the Bundesmann Test measure water absorption?

We use the Bundesmann principally to test the performance of DWR finishes. It’s a more demanding, and accurately predictive, test of water absorption than simple spray tests that uses a shower head to wet a rotating piece of fabric for ten minutes or more. Samples are then tested for dry times (and results compared to those we get from the field.)

What does the Killer Wash really do?

A low-tech wonder, our Killer Wash is simply a Maytag modified to churn, churn, churn until we kill the switch. Twenty-four hours is our usual minimum, the equivalent of 160 wash cycles in a home machine. The Killer Wash is more than an excellent test of the durability of laminates and DWR finishes; it gives good clues to a fabric’s overall ability to stand up to punishment in alpine conditions. It also tells us what components of a garment are prone to wear out before others (and thus need beefing up).

Does Patagonia measure dry times?

Absolutely. Wet and cold outdoors spells misery. Fast dry times are critical. Patagonia rejects many otherwise promising undershell fabrics for their slow dry time. Our test apparatus: a fairly sophisticated moisture analyzer that measures how many minutes a fabric takes to dry over 90-degree (body) heat.

What is a “Soft Shell”?

Simply put, Soft Shell is a concept, not a category. A soft shell, constructed of either a static or stretch fabric, will contain no waterproof barrier – breathable or otherwise. If internal moisture must turn to vapor to exit the shell, it is not soft. A soft shell is, by construction, highly water and wind-resistant and extremely breathable. Secondly, stretch woven garments that afford no effective wind resistance in mountain weather may be soft, but they ain’t shells: they’re gym clothes. Or we can think of it this way, choose your soft shell based on the level of exertion you will output for your intended activity. Consider the spectrum of highly aerobic (skate skiing, trail running) to stop and go (Alpine routes, fly fishing) and then make your purchase choice.

If you remember nothing more of this document, remember this one statement: A soft shell will, more often than not, allow you to stay drier longer, in a wider range of conditions, than its conventional hardshell counterparts. If you are still thinking, “ok, but for how many minutes will my softshell keep me dry?” then the point has been missed. So, before continuing, go back to the top of this paragraph and read it again.

As we said at the outset, technology is only a means.

Performance comes first.

That’s why we don’t use slow-drying elastic fibers in soft shell jackets (though we do in pants, which lie closer to the body as a heat source). That’s why our shell tops employ mechanical stretch weaves to achieve freedom of movement without slowing dry time – and thus diminishing breathability. Why we use directional linings to speed moisture transfer. Why we use exceptional – and long lasting – finishes to keep the surface dry in our proprietary Deluge™ DWR. And why we always use the best of the technologies available (and often have a hand developing them).

Patagonia & Gore-Tex- Where’s the love?

There is no question that Gore-Tex monolithic fabrics, especially XCR, are strong waterproof/breathables. In the history of waterproof/breathables they certainly set the standard for years – and that is precisely why we used them when they were at the top of the food chain. That said, from a development and testing perspective, today Gore-Tex fabrics are dated in terms of performance and price. To put this in perspective, consider our current H2No HB Stretch Element jacket and pants for comparison. The Stretch Element is not only noticeably more breathable than XCR in field trials, it is also very soft and has remarkable, stretch as compared to stretch fabrics which have what boils down to ‘cosmetic’ or ‘marketing’ stretch. Gore’s current technology, PTFE doesn’t stretch so we don’t expect to see dynamic stretch fabrics in Gore’s near future. Additionally we have found our own Deluge DWR to offer significant performance benefits over the DWR offered (and required by license to be used) by Gore.

Additionally, consider the changes that brought about XCR’s level of breathability: a serious reduction in the urethane topcoat applied to Gore-Tex. In fact, this is what changed early Gore from a highly breathable first generation to a not so breathable second generation. So can you guess what the remedy was? Correct, introducing XCR.

Add to this the wide variety of face fabrics and interior treatments (think 2.5 layer patterns and scrims, etc) that we have at our disposal with non-Gore product, coupled with the higher price on Gore, especially XCR and it starts to make sense.

So what it boils down to is better performance and value in our own technologies. We have no doubt that Gore will respond to the softening of their market with research and development which is why we keep ourselves open and not tied to single technologies. We insist on state of the art product – period. Things change too quickly to ride only one horse.

Why don’t we use Gore Windstopper?

Pretty much the same story here…we did use Gore Windstopper when windproof fleece was first developed in the late 80’s, early 90’s. In fact, in field trials it was noticeably better in terms of breathability. Today however, in our R4 jackets and vests, we have windproof fleece that is not only more breathable, but has remarkable stretch and softness. Remember, Windstopper is not Soft Shell and cannot be, given its current PTFE barrier technology. We have the capacity to control our barrier technology for different applications whether it be monolithic Hard Shell or Soft Shell – this is really important to us as this allows us to address the limitation that windproof fleeces manifest.

And Gore “Soft Shell”?

This is really simple…. it is not Soft Shell, its simply Gore-Tex with a brushed scrim that makes it softer on the inside. It’s just marketing. So Gore Soft Shell has little to offer the Soft Shell market. Gore can only throw marketing dollars at a game of semantics and hope to confuse the issue enough to become a viable player in Soft Shell. Again, hopefully they will throw their energies into some true Soft Shell product.

The limitations of the Lab

There are two inherent problems with all lab testing. First, good numbers can become ends in themselves (0 this, 100 that) and deflect from the central goal of making a great product, period. Lab data can become numerologically based mysticism.

Second, numbers can be manipulated, easily. Not only do specific numeric performance standards vary from fabric supplier-to-supplier and manufacturer-to-manufacturer, companies use a variety of equipment – and protocols – to test fabric attributes. In fact, most outdoor manufacturers don’t have their own serious testing facilities and have to rely on the word of others. “Spinning” the data, in a self-interested way, is not an unknown phenomenon. Other companies practice earnest science but go clueless when they try to correlate lab and field data. The upshot: you simply can’t usefully compare data from different companies. Always beware of numbers used for marketing, how they were derived – and what they mean.

Field Testing: What Happens When We Take the Product Outside

Many of our lab tests turn out to be keen predictors of performance. Comparing the specific criteria of one fabric against another in a controlled environment is a critical first step. But the true test – of how all these individual characteristics work in one garment – must follow in the natural world, and from a human being pursuing a real experience in actual conditions.

In-the-field testing of prototypes is critically important. You just can’t know how a fabric or garment performs until you try it out as it is intended to be used. Last year, we had 30 field testers put 203 prototypes and samples through the paces, all over the globe. Our testers are paid, trained and extremely skilled.

In the words of Duncan Ferguson, our long-time field-testing chief: “Our job is to endure some misery in the field so our customers don’t have to.”

On a bivouac in below-0 weather and howling wind, no one cares any longer about acronyms or numbers or charts or graphs, but whether a zipper works, a collar protects the chin, the body stays warm, the skin stays dry.

Only a handful of the prototypes we test make it into the line. Technology’s fine. But nature bats last. And she only reveals her power in the wild.

Endgame

And so we’ve come full circle. Technology and testing, the lab and field, checks and balances, yin and yang. We’ve left the marketing, the spin and the spray out. Instead you hopefully understand by now that we are absolutely committed to the pursuit of better and better products, achieving optimal benefits for their intended uses.

Yet, by this point, you may envision us as lab technicians in white coats. You may imagine mustached scientists in pleated trousers clutching electronic daytimers. Perhaps you are thinking of Church Ladies in long dresses and soft shoes. Well, truth be told, we’re still just phunhogs – climbers, anglers, paddlers and surfers, activists and athletes who through serendipity or otherwise, became fabric connoisseurs obsessed with building the best product and doing the least harm.

So, we’ll leave you with this: Patagonia is a product driven company, run by folks who, you may be surprised to find are just like you. We are never market driven. We are not corporate giants, owned by other corporate giants who have only initials for names. And, while we have no place on Wall Street, we do have shareholders: our resource base. Our shareholders have been celebrated by John Muir, photographed by Ansel Adams and described in the prose of Edward Abbey. Our shareholders have roots, rock and rhythms. Without them, we have no business, no future. And, here at Patagonia, we’re do business like we plan to be here for the next 100 years. Thanks for reading.

Addendum:

Test & Protocol descriptions:

Mullens Test- Mullens is a high-pressure test used to measure waterproofness up to 200 lbs. Per square inch

Hydrostatic Test- This is widely used worldwide for seam tape testing and low-level waterproofness. It applies 3 lbs. of pressure for two minutes.

Bundesmann Test- This is a very rough spray test. The normal spray test sprays a gentle stream of water from 4 inches above the fabric that has been angled at 45 degrees for approximately 10 seconds. The Bundesmann drops a heavy shower of large water droplets on a flat surface of fabric from 60 inches for a period of 10 minutes. We’ve adopted this test because our DWR’s passed the normal spray test too easily and we needed a tougher test that correlated better to actual field use. Our standard for Deluge DWR is a 90% rating (10% wetting) after 24 hours killer wash- a very, very tough test.

What is ASTM protocol? ASTM is the “American Society for Testing and Materials.” Almost every test method out there is written into an ASTM standard, most but not all have comparable EU and JIS (Japan) standards.